Investigating the Role of Market Incentives and Local State Actors for Group Forest Certification in Vietnam

By: Nga Thi Ha

Master of Public Policy

Crawford School of Public Policy

The Australian National University

Canberra, Australia

The Vietnamese Government has implemented far reaching policies and programs to increase tree cover by promoting plantation forestry. This has resulted in a current area of 3.4 million ha. of plantations, about half managed by smallholders and this is continuing to expand. This plantation resource in turn supports an industry contributing over US $700 million per year in export income, and contributing to the livelihoods of more than 1.4 million families (General Statistics Office of Viet Nam 2012; MARD 2014). To maximise environmental benefits as well as smallholder’s income and the broader economy of plantations, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a global leading sustainable forest management scheme, has been introduced and operated in Vietnam over last 20 years. However, despite of number of adjustments, the practical role of FSC with respect to meaningfully engagement and benefit creation for small-scale plantation owners in Vietnam is still questionable. There are currently about 5,000 ha. FSC certified belonging to smallholders in Vietnam, under the five group certificates awarded, with about 230, 000 ha. in total national certified forests up to June, 2017 (FSC, 2017). This achievement arguably represents a significant underperformance by FSC in Vietnam, given the considerable amount of donor subsidies and Vietnam Government support that has been provided. In fact, some actors such as forestry experts questioning the future of smallholder forest certification in Vietnam and indeed in Southeast Asia more broadly.

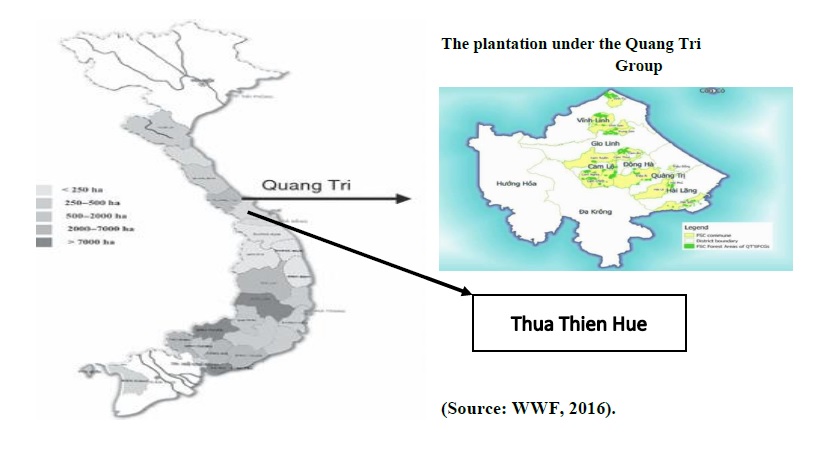

The underlying reasons for this situation have been examined by different scholars (e.g. Auer, 2012, Hoang et al., 2015). Research has focused either upon the interaction between FSC and the national government, such as the unfinished effort in finalising the Vietnam FSC standards after 20 years of cooperation, or upon local level challenges of connecting farmers to certification standards, with strong attention on technical complexity and certification cost issues. Very small growners of planted trees, of whom there are many, are discriminated against in current requirements for certification. My study focused upon a comparative case analysis of group certification processes for smallholders in two central provinces in Vietnam, the Quang Tri and Thua Thien Hue. My fieldwork results identified another explanatory layer for understanding the current opportunities and challenges of group certification in Vietnam, namely as involving the important role of provincial actors and local state institutions.

Forest certification has been conceptualised as a form of non-state market driven environmental governance (NSMD) (Cashore, 2002). The concept of NSMD can be understood as environmental regulation based upon ‘market pull’ that goes beyond the involvement of the state. However, my study shows that ‘market pull’ is still insufficient to fully drive smallholder Group Certification, while the involvement and support of Vietnam’s provincial government is pivotal. In Vietnam, key interactions involving FSC and state agencies extend beyond the central government and involve close articulation with sub-national actors and institutions. My findings are aligned with recent scholarly literature highlighting the re-centring of states in natural resource governance both in sustainability and legality (Gulbrandsen, 2014; Giessen et al., 2016).

FSC Group Certification in Two Case Study Locations

In my fieldwork, sponsored by the York University New Directions in Environmental Governance project, and the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), I focused upon two research sites in central coast Vietnam for understanding FSC Group Forestry Certification. The first involved the Quang Tri Group Forest Certification area (referred to below as the ‘Quang Tri Group’), which is managed by the Association of Quang Tri Smallholder Forest Certification Groups. The second field site involved the Thua Thien Hue Group Certification (referred to as the ‘Hue Group’), managing by the Forest Owner Sustainable Development Association (FOSDA). These two Groups share a number of similarities. Both were established through the combined organizational support of the World-Wide Fund for Nature in Vietnam (WWF) who has received significant supports from a number of donors such as the World Bank; German International Development Agency, GIZ; and IKEa Corpration; and their respective provincial Forestry Departments, under the approval of the relevant Provincial People’s Committee. Second, each Group received financial and technical support from Scania Pacific, a large, export-based wood processing company active in Vietnam, who also represents the timber purchaser for each Group. Lastly, each Group maintains the same general structure which includes a management broad comprised of provincial forest department governors, district, commune and village level leaders; and participating sub-groups of smallholder farmer tree growers, organised at the village scale.

The location of Quang Tri and Thua Thien Hue Groups

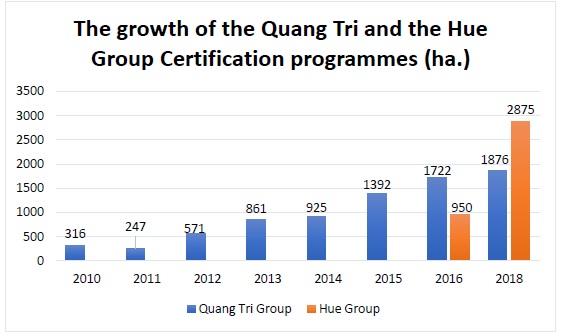

While there are many similarities between these two smallholder Groups as mentioned above, surprisingly, the pace of the expansion of these two Groups has been quite different. The Quang Tri Group has been characterised by a slow-pace of expansion (in terms of the number of farmers enrolled and the area of forest certified), from about 300 hectares in 2010 to just over 1,800 ha. in 2018, involving an increase of number of participating farmers from 118 to over 570 in the same period of time. In comparison, the Hue Group has enjoyed a much faster rate of growth, from a start in 2015, reaching nearly 1,000 ha. in 2016, and up to over 2,800 ha. in 2018, with the triple of number of participating farmers from over 200 to 600 people from 2015 to 2018. Their growth trend is depicted in Chart 1 below.

So, the questions are why the Quang Tri Group has developed so slowly, despite years of heavy donor support; and what has the Hue Group done differently to achieve a large and more rapid expansion. The next section will unpack these two questions.

Weak market pull and misperception of price premiums

The issue of ‘market pull’ for certified smallholder acacia plantation timber in Vietnam needs to be assessed in terms of international, national, regional and local contexts. My study identified that market pull was not sufficiently strong to support the rapid expansion of smallholder forest certification function in the Quang Tri case. The details can be found in my Masters thesis.

One issue relates to the misperception of price premium of FSC certified timber, which could be considered as a proxy for market pull, as it provides monetary incentives to plantation owners for applying FSC practices. The price premium is high under the both Group schemes, between 15-17%. This premium was reported as the most important incentive for farmers in applying FSC certification practices by all my key informants. Yet, in practice, the net benefits of this 15-17% gross premium, the amount actually enjoyed by a majority of smallholders with certified plantations, may just be around 5% (see also Flanagan et al., 2017). This is because the premium is only applied for saw-logs, which is the focus for the buyer. However, sawlogs typically account for only 30% of total timber production in an 8-year old plantation. The remaining 70% of the timber yield would usually be sold as lower value woodchips, at the prevailing market price, without any price premium.

Considered in this way, the net rewards of smallholder FSC certification are comparably more modest, in relation to the farmer’s time and labour in meeting the extensive technical requirements for getting their plantation ready for certifying. Here it must also be acknowledged that farmers have not had to pay for all associated costs to certification, which to date have been covered by donor partners (WWF, IKEA and Scania Pacific). These costs are reported as significantly high and beyond the capacity of the existing participating farmers to cover on their own (Laity et al., 2016, Nguyen & Tran, 2017, CIFOR, 2012).

An 8- year old rotation period is the unwritten norm that smallholders are advised to follow under the FSC practices, as this allows for the growth of larger diameter acacia trees, from which sawlogs can be cut for use in certified wood furniture manufacturing. The more common practice in central Vietnam is for a farmer to grow a 5-year plantation, in which the smaller diameter trees can be sold into the Chinese and Japanese woodchip markets (for which currently there is little demand for certified products). There are some exceptional cases in which plantation owners (largely cooperatives or better-off households) have been harvesting their acacia trees at year 10 or 12, which would yield much higher proportions of saw-logs, therefore generating more significant net returns from selling into the FSC sawlog market. The danger is that these atypical cases have become widely used in the promotional materials advertised by the WWF-FSC Group Certification proponents. While it is understandable that FSC plantation project proponents would tend to highlight more positive scenarios, this has also contributed to a misperception of the real benefits that FSC group certification could bring to smallholders, in terms of cash in their wallet. This issue of the real economic incentives offered by smallholder forest certification deserves greater attention by key actors, if they wish to make certification work for the practical benefits of smallholders. These financial benefits must also be considered in relation to farmer’s decision making and risk mitigation strategies, including the greater risks of growing longer term rotations due to natural disasters; and the problems of smallholder farmer cash flow, whereby other pressing livelihood needs can work against long rotation plantation forestry (including expenditures on housing, children’s education and employment, and urgent events such as medical care (Pincus, 2012, Field Interviews, July, 2017).

Inadequate support by Provincial Governments

My study also found that provincial-level governments could exert both indirect and direct influence on the development of the Group certification, in many ways. In fact, the support provided by the Quang Tri provincial government, including that of the People’s Committee and other government agencies in the forestry sector, such as Forestry Protection Department (FPD), have been under expectation, and this issue is identified by some for the slow diffusion of this Group over the last 8 years (Field Interviews, July 2017).

At a broad level, the Quang Tri Provincial People Committee (PPC) has demonstrated a limited interest in supporting the development of forest certification, by not placing the program within the five-year Social-Economic Development Plan (SEDP) for the provincial forestry sector. In Vietnam, the SEDP represents the clearest roadmap for provincial department priorities, and provides the best reference for district and communes in releasing their annual and five-year SEDP resolutions. In an effort to increase provincial revenue, which is almost always in shortfall, the most recent Quang Tri SEDP issuing in 2017, indirectly identifies priority forest sector support for woodchip and medium-density fibreboard (MDF) wood panel factories, rather than for wood furniture production through its infrastructural development strategies. Currently, Quang Tri manufacturing capacity for woodchip and MDF (using short rotation, non-certified timber) represents about 700,000 cubic meters annually, about 4 times higher than the existing (certified and non-certified) demand for sawlogs for wood furniture production at about 180,000 cubic meters.

These figures become more pronounced when we consider the production capacity of factories that are under construction in Quang Tri province of over 800,000 m3 and 20,000 m3 annually for woodchip and furniture production respectively (Quang Tri DARD, 2015). The implication is that the Quang Tri PPC is placing priority support behind a form of wood processing that uses short rotation, non-certified timber. This overall policy direction is at odds with the national-designed policies in promoting long rotation and certified plantations. Particularly, this well demonstrates the case that in Vietnam, centrally-designed policies may not be accompanied by sufficient resources, and rather leaves implementation to sub-national governments, which may not share the overall strategic perspective. Moreover, despite the significant advocacy efforts from WWF in engaging the Quang Tri PPC into supporting for forest certification for smallholders, the provincial government’s actual policies shows other priorities.

Regarding direct involvement of the leading government agencies in forestry sector, Department of Forestry Development (Chi cuc Phat trien Lam Nghiep) which was emerged into Forestry Protection Department (FPD, Chi cuc Kiem Lam) since 2015 by the national policy, also plays a critical role. The FPD is involved in three main stages of the FSC smallholder group development, including: initial establishment, current operations and future growth, in which the last two are most important. The key staff in the Association’s management board are the provincial governors, who (as alluded to above) wear several hats. The same principle is applied at the village level. Therefore, the Group is operating at almost no employment cost. More importantly, these concurrent governors in the management board have political powers which could drive or constrain the growth of the Group. In one case, a district governor in Quang Tri province, who is particularly interested into forest certification, has shown his goodwill and commitment through various forms of directives, guideline and annual targets for communes and villages which result in a significant expansion of area participating into the Group in that district (Field interviews, July 2017). This highlights the importance of the political powers of government officials, and their meaningful engagements. The challenge is that the abovementioned governor is an exception, and the Quang Tri Groups needs more than one such patron to support its growth.

In the matter of future diffusion of the efforts of the Quang Tri Group, key informants highlight that the role of local state authorities needs to be made more meaningful, with a greater sense of ownership, as compared to the current situation characterised by modest responsibility and ownership. In responding to the question of ‘How likely is the Quang Tri Group will reach their target of certifying 3,500 ha. by 2020?’, the Association’s staff stated: ‘It is next to impossible to obtain that target unless more appropriate attention and financial resources from Provincial People’s Committee are allocated to do so, as we have limited resources for further expansion’. A similar response was found from WWF, who emphasised that ‘WWF resources as a project are limited. We have been looking for more active responsibility from the provincial government’ (Field interviews, July, 2017).

What has the Thua Thien Hue provincial government done differently?

My study argues that the noticeably higher growth rate of the Hue Group is a conjuncture of many factors. The high level of commitment and interest from provincial and village state authorities towards FSC Group Certification for smallholders in Thua Thien Hue was particularly highlighted.

Firstly, the development of the Hue Group is one of key objectives of Thua Thien Hue Provincial Forestry Protection Department (FPD). They aim for both meaningful horizontal and vertical engagements and cooperation of associated departments in the forestry sector, through policies and directives to support the Hue Group. More essentially, the FPD and the Hue Association, FOSDA, who is in charge of the Hue Group’s development, have also deliberately tried to mainstream other current external supports both in finance and government policies to implement FSC certification for smallholders. The FOSDA’s chairman claimed, “It could be a waste if we do not mainstream FSC certification into the process of completion for the government task of transformation plantation. By integration, farmers would be greatly benefitted” (Field interview, 15th July 2017).

Secondly, there has been a signal of positive changes in the attitude of provincial states, from a project-driven approach, which is still heavily dominated in Vietnam, into a government program approach or provincial authority tasks in applying FSC Group Certification for smallholders, which can be seen clearly from FOSDA’s chairman. Furthermore, they also aim to change the mind-set of local officials, village heads and farmers into this innovative attitude of provincial authority tasks. This attitude change is significant because of decision-making based upon project-driven mind-sets, such as high dependence upon external intervention, and a lack of a sense of ownership, have negatively deterred the success of many programs in Vietnam The government program approach here refers to positive traits, to encourage farmers to have a sense of ownership, a long-term responsibility towards their participation, and a sense of security, which are crucial for the successful post- WWF expansion of the Forest Group certification. Unfortunately, my research identified that a project-based attitude still dominates the Quang Tri Group, and from my field observations and interviews, this has influenced negatively on the certification Group’s development in that province.

Conclusion

My study has revealed that the current highly hierarchical structure of the Vietnamese government, at all levels, could significantly constrain the development of FSC forest certification for smallholder initiatives. In particular, provincial level governments, with their strong political powers and authorities, appear to act as crucial sources of influence over FSC Group Certification development for smallholder plantation growers in Vietnam. This ‘political’ aspect deserves more attention from associated actors who aim for support smallholders in applying for market-based schemes such as forest certification, particularly in contexts where the ‘market driver’ is not fundamentally strong, there are relatively modest monetary incentives, and the external support from international NGOs and donors is on the decrease.

Bibliography

Auer, M, R 2012, Group Forest Certification for Smallholders in Vietnam: An Early Test and Future Prospects, Human Ecology, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 5-14.

Cashore, B 2002, Legitimacy and the Privatization of Environmental Governance: How Non- State Market-Driven (NSMD) Governance Systems Gain Rule-Making

Authority, Governance, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 503-529.

Flanagan, AC, Midgley SJ, Stevens, JM & McWhirter, L 2017, Smallholder Tree-Farmers and Forest Certification in Southeast Asia: Productivity Requirements and Risk Profiles, Springer, forthcoming.

General Statistics Office of Viet Nam 2012, Results of the Rural, Agriculture and Fisheries Census in 2011, Statistical Publishing House, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Giessen, L, Burns, S, Sahide, MAK & Wibowo, A 2016, From governance to government: The strengthened role of state bureaucracies in forest and agricultural certification, Policy and Society, vol.35, pp.71-89.

Gulbrandsen, LH 2014, Dynamic governance interactions: Evolutionary effects of state responses to non-state certification programs, Regulation & Governance, vol.8, pp.74–92.

Hoang, HTN, Hoshino, S & Hashimoto, S 2015a, Forest stewardship council certificate for a group of planters in Vietnam: SWOT analysis and implications, Journal of Forest

Research, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 35-42.

Laity, R, Flanagan, A, Ho, H, Nga, H & Ho, VC 2016, Leveraging Sustainability with Profitability: Verification Mechanisms for Smallholder Plantations in Vietnam. A contribution to ACIAR project FST/2008/039 “Enhancement of production of acacia and eucalyptus peeled and sliced veneer products in Vietnam and Australia”, Australia.

MARD 2014, Decision No. 3322/QD-BNN-TCLN dated on 28 July 2014 on approving national forest status for 2013, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Hanoi, Vietnam.

Nguyen, TTM & Tran HT 2017, Economic efficiencies of the forest certification group in Trung Son commune, Gio Linh district, Quang Tri province, Hue University Journal of Science, vol.113, no.14, pp. 127-136.

Pincus, J 2012, Prosperity in Depth: Vietnam’s reforms, the road to Market Leninism, Legatum Institute.

Quang Tri Department of Agricultural and Rural Development 2015, Report no.787, Status of factories producing and trading timber products in Quang Tri province, (unpublished).

WWF (World Wild Fund), 2016, Administration Handbook, association of households with forest certification in Thua Thien Hue, WWF (unpublished).